April 21, 2020

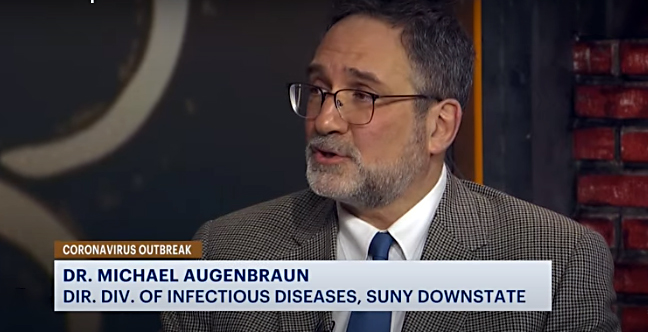

A few weeks ago, the scene inside the emergency department at Downstate Medical Center’s University Hospital was something that Dr. Michael Augenbraun could never have imagined in his long career as an infectious disease specialist.

Desperately ill people, sickened by the coronavirus, were everywhere. Some of them were already near death. They were arriving in such numbers that the staff could not register them, evaluate them and treat them fast enough. It was a modern-day version of a Medieval plague, with all its horror and hopelessness, dropped into one of the poorest parts of the nation’s largest city.

“Up until the third weekend of March, it was like a charnel house here,” said Augenbraun, director of the hospital’s infectious disease division, and a UUP member. “People were rolling in, and there was not a lot we could do for them.”

Now, there may be some hope for the sickest COVID patients. At Downstate, as well as at the two other SUNY teaching hospitals—Stony Brook University Hospital on Long Island, and Upstate Medical Center Hospital in Syracuse —doctors are participating in a national effort to try a century-old treatment on COVID patients.

In the midst of a pandemic caused by a disease which has no vaccine, no cure and few certainties—and which had, through mid-April, killed nearly 40,000 people in the United States—the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has authorized hospitals around the country to begin convalescent plasma therapy.

Doctors turn to Downstate staff

Convalescent plasma therapy involves giving a transfusion of blood plasma from people who have recovered from COVID-19, and therefore carry antibodies to the coronavirus in their bloodstream, to patients still sickened by the disease. It has been used to treat a range of serious diseases, including diphtheria, an often-fatal bacterial infection that especially targeted children before a vaccine was developed a century ago.

At Downstate, Allen Norin, an immunologist and UUP member who leads the convalescent plasma workgroup for COVID-19, enlisted the help of UUP Chapter President Row ena Blackman-Stroud to get the word out to the staff—many of whom had contracted and recovered from COVID-19—that the hospital needed staff members to consider being plasma donors. They would be a ready source of plasma, reasoned Norin, and would be likely donors because of their vivid understanding of the damage wreaked by the coronavirus.

That’s just one more way that Downstate members are coming through in this crisis, Augenbraun said.

“Every day, I’m encouraged to go in, because of the people I’m dealing with,” he said of the medical and support staff in the emergency department and intensive care units. “We really appreciate the union getting the word out; we really think our strength is in our staff.”

We really appreciate the union getting the word out; we really think our strength is in our staff.”

An urgent response

There is no certainty that convalescent plasma therapy will work; there is only a handful of case reports about patients in China and Korea who showed improvement after receiving plasma treatment. In mid-April, Downstate was just starting to solicit plasma donations and had not yet started administering the therapy. And it was still too early to know the results of the treatment in the United States.

The urgency of the situation has fast-forwarded the medical response, and so this effort is not being handled through the usual, and slower, approach of a clinical trial, said Norin, who in normal times oversees the kidney transplant laboratories at Downstate and Stony Brook University Hospital.

“In my view, it’s not a trial unless there’s a control group,” Norin said. “This is a treatment approved by the FDA.”

Norin was especially enthusiastic about the convalescent plasma therapy because he knows from personal experience that it can work.

Eight years ago, his infant grandson contracted botulism, a potentially fatal infection caused by a bacterium found in soil, when the baby put his hand into some dirt and then into his mouth. The botulism bacterium leads to the buildup of a neurotoxin in the body, but Norin’s grandson responded to a transfusion of plasma donated by someone who had survived the infection. Today, he’s a healthy, active 8-year-old.

Union members strong, stalwart

An effective treatment is needed now, but also for the strong possibility that there will be another coronavirus outbreak in the country before a vaccine is developed. Estimates on the production of a vaccine range from at least a year, to several years.

“We have to figure all of this out, because this is telling us, ‘There is more to come,’” Norin said.

About 200 people have died of COVID-19 at Downstate since early March, Augenbraun said. Although the disease appears to have peaked in New York City, there are still many very sick people in the hospital.

“It’s been a struggle for weeks,” he said. “We’re getting a little bit of respite now, but the whole thing is unpredictable.”

So is the convalescent plasma therapy, but he said in an April 17 interview that he hoped to start the treatment within a week.

“We really appreciate the union getting the word out,” he said. He’s been too busy, and too exhausted, to directly deal with UUP’s statewide officers on the situation at the hospital, but “the people they represent have been a saving grace through all of this,” Augenbraun said. “They really are heroes.”